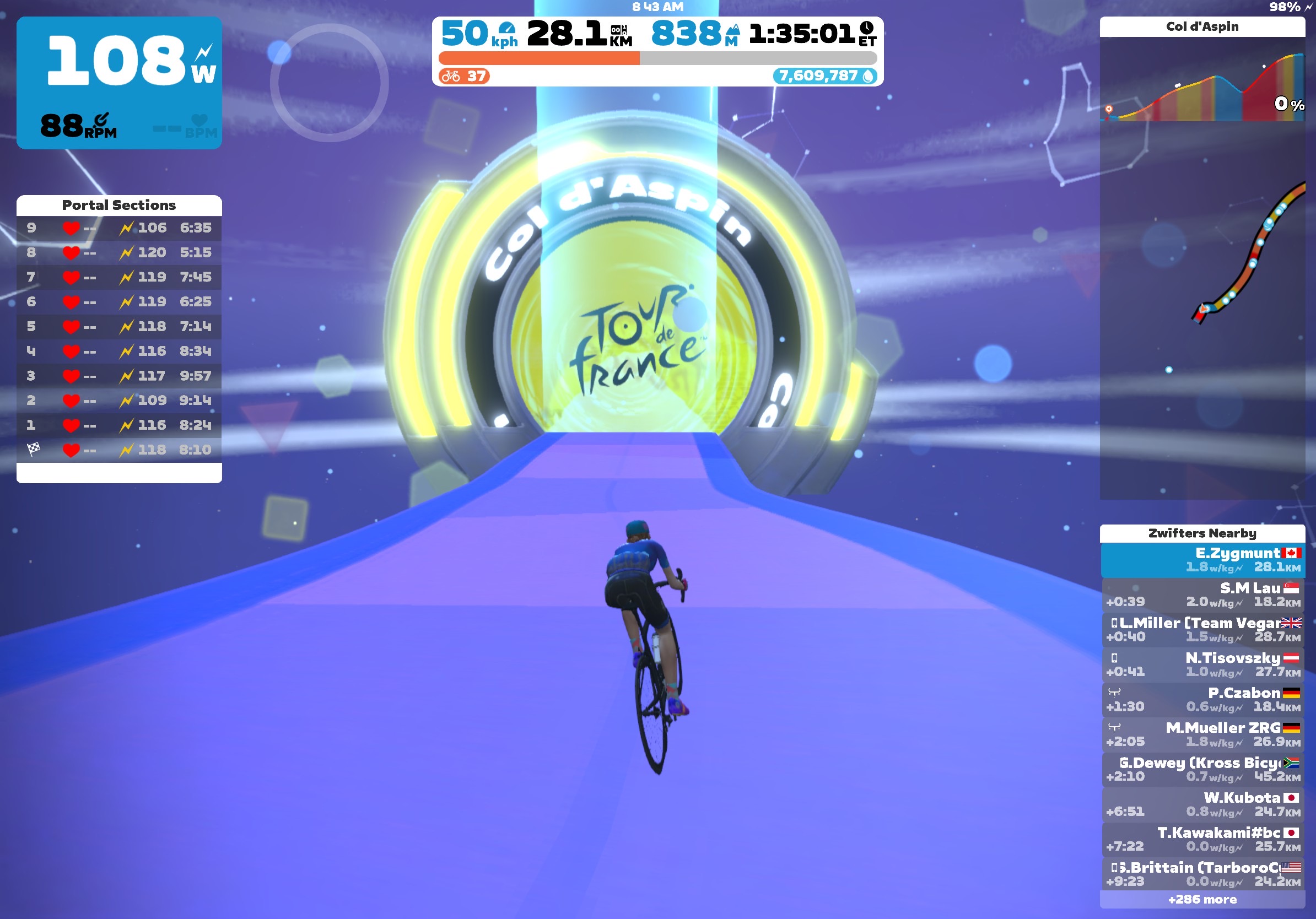

It's the Sweat that Keeps Me Clean

By Ellie Zygmunt13,420 km

It’s August again, which means once again I’m nursing an injury. It seems I’m cursed to sacrifice some skin to the sun god every summer. This year’s ceremony involved an ungainly trip over uneven sidewalk on what should have been an easy run. I made a four point fall, skidded on my palms, and had to walk home with blood dripping down my shins.

This isn’t the first time I’ve debrided my own road rash in a shower and I doubt it will be the last. Sluicing blood from my palms and delicately extracting gravel from my kneecap is a Summer ritual at this point.

While grateful that my flesh wounds aren’t worse and I was spared a sprained wrist, I’m rueful that I didn’t just go for a bike ride instead. People rarely look confident, self-possessed, or happy while running. Meanwhile, it’s exceedingly easy to look rad and enjoy your life while riding a bicycle. For the last 6 years I’ve mixed outdoor rides with liberal doses of Zwift, an indoor cycling platform, but my habit dropped thanks to moving cities and downsizing spaces. My road bike has been hanging in storage for months while my partner and I played FurnitureTetris. But now that I am tender, bandaged, and nursing a fresh grudge against my neighbourhood’s sidewalks, I look to my bicycle and trainer with tender affection.

0 km

I signed up for Zwift in August 2019. Another August, another injury: a concussion earned in figure skating practice. No outdoor cycling for at least 6 weeks, but I should, advised a colleague of a friend from the Kinesiology faculty, find a way to continue exercising to help my brain recover faster.

Zwift had blanketed that year’s Tour de France coverage with ads. The clips were sleek but cheerful. Players pedalled their road bikes under kaleidoscopic projections of an idyllic tropical cycling paradise called Wattopia. That Summer’s campaign also featured a cheeky Geraint Thomas cameo, the 2018 Tour champion daring the would-be player to join him for a virtual spin.

“Fun is Fast” said the tagline.

My skepticism was considerable when I signed up for Zwift. I would rather eat a bag of spiders than sweat it out in a room of strangers spinning by candlelight while an instructor spouts new age fitness quotes, so I’d never found a place in spin classes. Previous solo attempts at indoor cycling were underwhelming and soporific: there is no podcast or tv show compelling enough to break the monotony of cycling inside. I’d spin the wheels but hated every second. But I was desperate to ride and keen to give my poor brain a better shot at healing. I hacked together the cheapest set-up possible from scavenged and borrowed gear. I spun up.

12.71 km

My first Zwift ride was the Greater London Flat route. 12.71 km in 26:45. I don’t remember much about the ride’s scenery, but I do remember the effort. I remember wondering whether my legs or my bluetooth sensor were broken, because those were the only possible explanations for why riding the first six virtual kilometres felt like riding uphill through hot glue. I felt like my entire body was being melted and reforged.

As I pedalled through the glue pit of my first Zwift outing I was dazzled with new measurements, icons, abbreviations, and environments. I was spinning harder than I’d ever done in my life and I was still getting dropped by everyone on the digital tarmac.

I rode 12 more times before the month was out.

497 km

“So you play a video game by riding?” asked incredulous friends and acquaintances. “You bought an exercise bike to game with?”

Your Zwift avatar cycles through an array of virtual worlds designed to offset the visual monotony of riding indoors. The basic Zwift set-up involves a bicycle, a trainer, and a device with which to run the game. Your bike is attached to a trainer, and the game signals the trainer to raise or lower the resistance to match the elevation and terrain you’re virtually riding. More elaborate trainers or full fitness bikes can simulate the rumble of rolling over cobbles, the extra drag of dirt and gravel, or steeper slopes.

Zwift promises “endless roads” and delivers them via a rotating carousel of virtual landscapes. There was the aforementioned classic, Wattopia, a glow-up of Zwift’s original map, Jarvis Island. In the early days of the game, Jarvis Island was the only world on offer. Even more monastic, there was only a single route, meaning early players would grind lap after lap of this circuit, week after week. That one route was compelling enough to build an indoor training empire. By the time I rolled up, Zwift had expanded considerably: the London and New York maps offered surreal and idyllic city escapes, while recreations of the World Championship routes from Richmond and Innsbruck offered the chance to imagine you were sprinting against the pros in the bell lap of your mind. Throw in a punishingly steep replica of Bologna’s San Luca climb and there was a properly prickly time trial option. It was a feast.

There is no shortage of virtual cycling programs that promise fitness gains and “immersive experience.” Where Zwift succeeded and other indoor training methods failed was by perfecting the precise blend of gamification and conviviality that makes riding a bike fun. The moment your will starts to fade Zwift delivers an incentive to keep going. A pop up box announces there’s a sprint in 800m, or that you’re this close to beating your previous lap time. Fellow riders can tap a thumbs up icon next to your name and give you a Ride On, a micro-dose of encouragement when your legs feel like they’re about to blow. Rolling through route checkpoints grants XP bonuses and power ups. Five more minutes becomes two more kilometres becomes whoops it’s time to check the chain wear.

575 km

I signed up for my first Zwift Academy, a multi-week training camp, in September 2019, . It was a rude introduction to the first real cycling training I’d ever experienced. Every weak point in my technique was brutally exposed. My low cadence, paltry climbing skills, and mediocre sprint were all revealed over the course of diagnostic ride that left me flopping over the bike with all the grace of a gutted fish. Zwift Academy was one of the most physically taxing things I’d ever done, and that was at end of Event 1 of 8.

Over the next few weeks I’d don my sweatband, grit my teeth, and ride through hot glue pit after hot glue pit on my way to glory. I started recognizing people in the chat, we started following each other, and a little club started to form. People shared their workout playlists, fuelling tips, and stories of clipless pedal fails. If I saw a mutual was signed up for a particular group ride I’d feel the twinge of missing out and start hunting for my last clean pair of shorts. Time to clip in.

It’s fashionable for apps, and especially fitness-focused apps, to claim they’re fostering a community when they’re really just assembling a subscriber base they can juice for recurring revenue. The community in Zwift is an essential part of the user experience, not an afterthought. When you start your ride everyone around you appears in a sidebar: first initial, last name, and a tiny flag. Everyone is mixed together, from utter noobs on rusty mountain bikes in suburban garages, to UCI pros doing a light spin after a training camp ride in Mallorca. You can see the distance and power readings from the riders around you, making it easy to self-select into a pace-friendly group. “Blobbing up” lets the group go faster and induces intense, brief comradeships. People cheer each other on in the chat, bitch about the weather, or enthusiastically call out the cities they’re riding in. You’re all just trying to get through the last 10km together.

I have a list of riders I follow from around the world, many of them going back to that very first Zwift Academy. I’ve ridden alongside them through Fondos, ramp tests, and time trials. My phone lights up at all hours to let me know when they’ve started spinning. Evening in Vancouver means midday for the Japanese, Kiwi, and Aussie contingents sneaking in a midday lap. The Europeans are all out when I reach lunchtime. Us North Americans log in last, commiserating about the deep freeze of Edmonton or hurricanes in Florida. You’ll follow a random guy from Sweden after a group spent in the same blob and give them ride ons for years, suddenly privy to the timing of one part of their day. These strange intimacies are encouraging and hopeful. You’ve seen each others’ heart rates and shared a measure of the same struggle: you were all grinding up the Alpe du Zwift, you know the sizzle of a lactate overload and the soul-frying effort of ascending a 19% grade. You’re in it together. Even the lone riders, without pace partner, clubmate, or group, will be showered with ride ons from strangers spinning the same routes.

1,000 km

Zwift doesn’t hide the fact that you are playing a game. The routes and worlds are stylized and embellished with playful touches rather than hyperrealistic renderings of the real world. This causes some unnerving moments of vertigo and compression. If you are familiar with the real geography of London you will feel the uncanny frisson of riding over Tower Bridge and arriving at the base of Box Hill, an impossible geographic mashup. Zwift’s New York takes the idea of the High Line and pops a sci fi filter on it, lofting a rider through elevated roadways with hovercars in the distance. Riding through the neon-lit arcade of the Neokyo level elicits delight that’s impossible to replicate on a real ride through Tokyo.

“But it must be easier than riding outside. It’s not REALLY riding,” scoffed another friend. This person has half a point: riding in Zwift is much easier than riding outside because no one is getting doored in Wattopia. Players share the road with each other and a few NPC vehicles thrown in for set dressing, but the vehicles always give way to riders. The pedestrians are happy, too: the game’s auto-tracking programs ensure that there are no traffic conflicts between cyclists and runners.

The greatest and most alluring artifice in Zwift is the lack of cars. There are very few stretches of pavement anywhere I’ve lived where it’s practical or safe to really crank out the speed and power that a road bike can generate. That limitation doesn’t exist in Zwift. Zwift Insider, the official unofficial guru of all things Zwift, documented riding the real Box Hill to compare to the virtual equivalent. The verdict: “I was stuck behind a car and literally had to ride holding the breaks [sic], I was caught by a mountain biker. I turned to him and commented, ‘It’s more fun on Zwift!’ He agreed.” By imagining a world without cars, Zwift opens a portal to a beautiful alternate dimension where nobody has to die because some dipshit can’t pay attention to the road. A deep part of Zwift’s appeal is in it’s abnegation of the automobile.

Zwifting is also nothing like riding outside because it’s several times harder than riding outside. There is no coasting and almost no freewheeling. Stop pedalling and you’ll have to kick over all 16 pounds of your trainer’s flywheel from a dead stop in your last unlucky gear, which will feel like trying to run with a turkey strapped to your leg. The running joke among Zwifters is that your “recovery” ride will easily see you sprinting in Zone 4 to catch a group of Dutch punters who sassed you in the chat as they bombed by. “Light spin” means, “accidentally signing up for a crit race to win a heart attack and a last place finish.” As one memorable Reddit post put it: “I tried to keep up. My avatar looked like it was trying to escape a burning building. Meanwhile, some Belgian guy typed ‘EZ warmup’ in the chat. EZ. Warmup. I was at 187 bpm and breathing like a vacuum cleaner someone had spilled soup into.”

1,700 km

Every time I try to explain Zwift’s appeal I sound like I’m recruiting for a cult. “You will experience phenomenal power and exercise endorphins! You will struggle! You will sweat! You will mortify your flesh in spandex and sweatbands! You will emerge stronger! All for a low, low monthly fee!”

I felt far less like a failed door-to-door salesman and more like a visionary by March 2020. Once it became apparent that this pesky flu thing might be a problem for more than a few weeks, everyone started scrambling for socially-distanced workout routines. Trainers went out of stock, along with anything remotely related to a bicycle, from brake pads to bluetooth power meters. I was set to sweat away lockdown and emerge triumphantly buff butterfly.

Then I started having panic attacks on the bike.

In May 2020 I assumed feeling a li’l nervous was everyone’s resting mental state. I was working under the threat of layoffs and carrying the responsibility of three employees worth of work for 30% of the pay. I was drinking four coffees a day and sleeping 4 or 5 hours a night. I was doing just great, thanks, let’s all keep banging the pots for those first responders.

I was riding the last segment of Alpe du Zwift when I felt my heart detach from my chest and ping pong around my torso. My heart rate runs high under normal circumstances, but it does not normally crack 210 bpm on a steady effort. I felt breathless and terrified, leaden with the dread true crime victims describe right before their assailant jumped at them with a knife drawn. An animal unease, the kind that makes a cat scream and run.

An emergency room during second wave, pre-vaccine Covid was a deeply distressing place to be. If I didn’t have anxiety going into the ER I sure as shit did after being masked up and wheeled in for a cardiac assessment. The verdict: anxiety-induced supraventricular tachycardia.

“It can’t just be anxiety, I’m so calm,” I argued with the ER doc as he detached the dozens of wires running from the sticky ports on my body to an EKG reader.

“You’re also dehydrated,” he said, “We’ll send you home once your IV runs through.” He handed me over to the nurse.

“Anxiety?”

“It’ll do that,” she said, “Want to go for a walk?”

I tottered around the ER arm-in-arm with my nurse and an IV stand while she told me about her past life competing in biathlon and her own history of panic attacks. A case of the jitters is a real liability when you need to shoot straight. She gave me tips: cut the caffeine, try box breathing, talk to a therapist, and have a backup Ativan prescription.

“Keep on breathing, get some sleep, and it should resolve on its own.”

Only it didn’t.

I clicked into my pedals a week after my ambulance ride. But the sight of my rising heart rate—normal! Climbing a hill!—brought back the screaming dread. I stopped, tried to breathe in a square and think of a quiet place in my mind where Covid didn’t exist and french fries were free. Every time I started pedalling again my heart rate would spike and my panic would too. Riding my bike on Zwift was one of the few things keeping me sane in the Spring of 2020 and now it was the source of my anguish.

I tried every sports psych and self-talk trick I could find. All of them failed. The only solution was to literally hide my heart rate. I would cover my watch face with the cuff of my glove. I taped a post-it note over the Zwift HUD on my iPad screen to prevent myself from accidentally seeing the number. As long as I couldn’t actually see my heart rate measurement, no matter how hard I was working, my panic stayed back.

Zwift was worth the risk of psychic damage for the fitness and the solidarity of spinning alongside thousands of other cyclists in a virtual nirvana. I could have taken up running, but I refused to stoop so low and quit riding. I cycled with my stupid post-it note blindfold for 3 years, until I finally took the advice Nurse Biathlon had given me in the first place: talk to a professional. After a series of sessions spent systematically disarming my anxiety triggers, my new psychologist gave me homework: “Peel off the post-it note.”

6,500 km

“Zwift is silly!” argue cyclists who pride themselves on grinding out their training miles in freezing rain and apocalyptic heat waves. When they aren’t riding into a headwind strong enough to break a Dutch windmill, they’re scrutinizing every gram of their kit and agonizing over insufficient sock height. This species of roadie insists on maintaining an elevated aesthetic that prizes sleekness above all. Shoes must always be spotless and, preferably, white. Everything should have as much carbon as chemically possible. “Souplesse” is the name of the game. Every sport draws a caricature of it’s worst impulses, and for roadies, those flaws are overweening pride and status-conscious neurosis.

Road cycling is a deeply silly sport. We ride a slice of carbon and aluminum downhill at 60+ km/h with feet locked to the pedals. We give gigantic smoked hams and wheels of cheese as race prizes. And you have to wear the right socks or your mates will never let you live it down at the cafe stop. It’s a silly sport for serious people.

Zwift understands this truth. You ride hard in a playful environment. Its primary colours are orange and hot pink. Zwift’s mascot is Scotty, a chubby squirrel sporting a cycling cap. There are holiday rides where your kit is a Christmas sweater or you slowly acquire pieces of an inflatable dinosaur costume for each chunk of mileage you complete. Your reward for completing the game’s steepest challenge, cycling the equivalent elevation of Mount Everest twice, is the Tron Bike: a neon-lit frame that rolls like a portable rave and is one of the best bikes in the game. Progress is measured in drops of sweat (which you can use to purchase game upgrades) and the number of pizza slices burned. One of the most iconic clubs in the game is The Herd: members identify each other by mooing in the chat. All the while, no one sees your sweaty face but you and your in-game avatar can wear whatever sock height they damn well please.

Fun is fast.

13,000 km

I hesitate here: am I expressing too much enthusiasm for a subscription-based e-sports platform? What’s stopping Zwift from taking all of our money and funnelling it into a military AI startup or right wing think tanks? So much technology feels soulless, isolating, and exploitative that it’s surprising to encounter a genuinely useful and delightful piece of tech. I keep waiting for the rug-pull, the moment where I have to pay for an upgrade to avoid an in-game ad break or when bumping up a subscription tier unlocks an AI-powered chatbot that heckles my efforts like an ultra-salty Eddy Merckx.

Zwift, despite taking in a large amount of venture capital funding, seems to be evading the pitfalls of that funding. CEO Eric Min deftly talked around AI integration in an interview with DC Rainmaker and Zwift as a whole appears to understand that the platform’s appeal is actually building useful stuff that people want: more routes, more fun, incentives to keep training and plans to build fitness, and solid stand-alone hardware. Building useful features shouldn’t be a revelation at this point, but in the race to the bottom of the SaaS barrel via the devil’s bargain of specious AI “integration”, a tech platform actively choosing to build for users first feels as refreshing as a cold mini can of Coke at the end of a race.

Also encouraging: Zwift’s hefty investment in women’s cycling as the title sponsor of the Tour de France Femmes. Since 2022, Scotty has presided over a revived women’s tour, a racing spectacle that’s growing stronger with each edition. This year I watched Pauline Ferrand-Prévot seal the deal with at thrilling final stage win, then rolled on down to a street festival with friends. I was introduced to the friend of a friend who, upon learning I watched road cycling, proceeded to express his admiration for Sarah Gigante’s heroic effort on the day’s stage. Someone other than me knew who I was talking about when I said “PFP”! Someone other than me was watching a women’s bike race!

Dear Zwift, if you’re reading this: please don’t make an Eddy Merckx robo-heckler. Please do send me a plush Scotty.

13,451 km

The post-it blinder is long gone. I haven’t had a panic attack in years. Though I have spells away from the saddle, I always return. Bicycles have been far more supportive, emotionally dependable, and useful than any of my ex-boyfriends and several family members.

I continue to somehow be surprised that virtual riding works. Zwift did more to improve my practical fitness and cycling skills than years of aimless outdoor riding. I finally learned how to pace myself on climbs and when to drop the hammer on a sprint. I learned, painfully, at what kilometre count I will bonk if I’m not fuelling properly. True, there is no draft bonus waiting from me at the top of my local climb, but I have the mileage in my legs to know I’m going to make it to the top. Tell me Zwift doesn’t work as I drop yet another lycriste with my steel touring bike.

The ting of sweat hitting the floor and my post-sprint gulping wheeze are sweet sounds to me. If you love sports, and I certainly do, the training, effort, and competition are deeply satisfying. Getting in the zone on a bike is like playing in the pocket with a band: effortless, effervescent, soul-stirring, and transcendent. You will suffer whatever pain is required to find that pocket again and again. Bicycles are extremely effective at delivering that bliss even as they extract your sweat and flesh. I write this with my palms salved and wrapped to protect my latest case of road rash. I fear no future crashes: the pursuit of bliss means more than the threat of any blood or terror.

A friend of mine has a t-shirt with the slogan “Enjoy the Inconvenience!” emblazoned across the back. I’ve organized my apartment around making space for my Zwift set-up, even if that means a less than elegant arrangement. My road bike sits vertical next to my bed when not in use, gravity optimizing precious square footage. I find ways to keep going and enjoy the inconvenience. It’s the sweat that keeps me clean.