Exiting the Stream

By Ellie ZygmuntYou’ve probably heard this one:

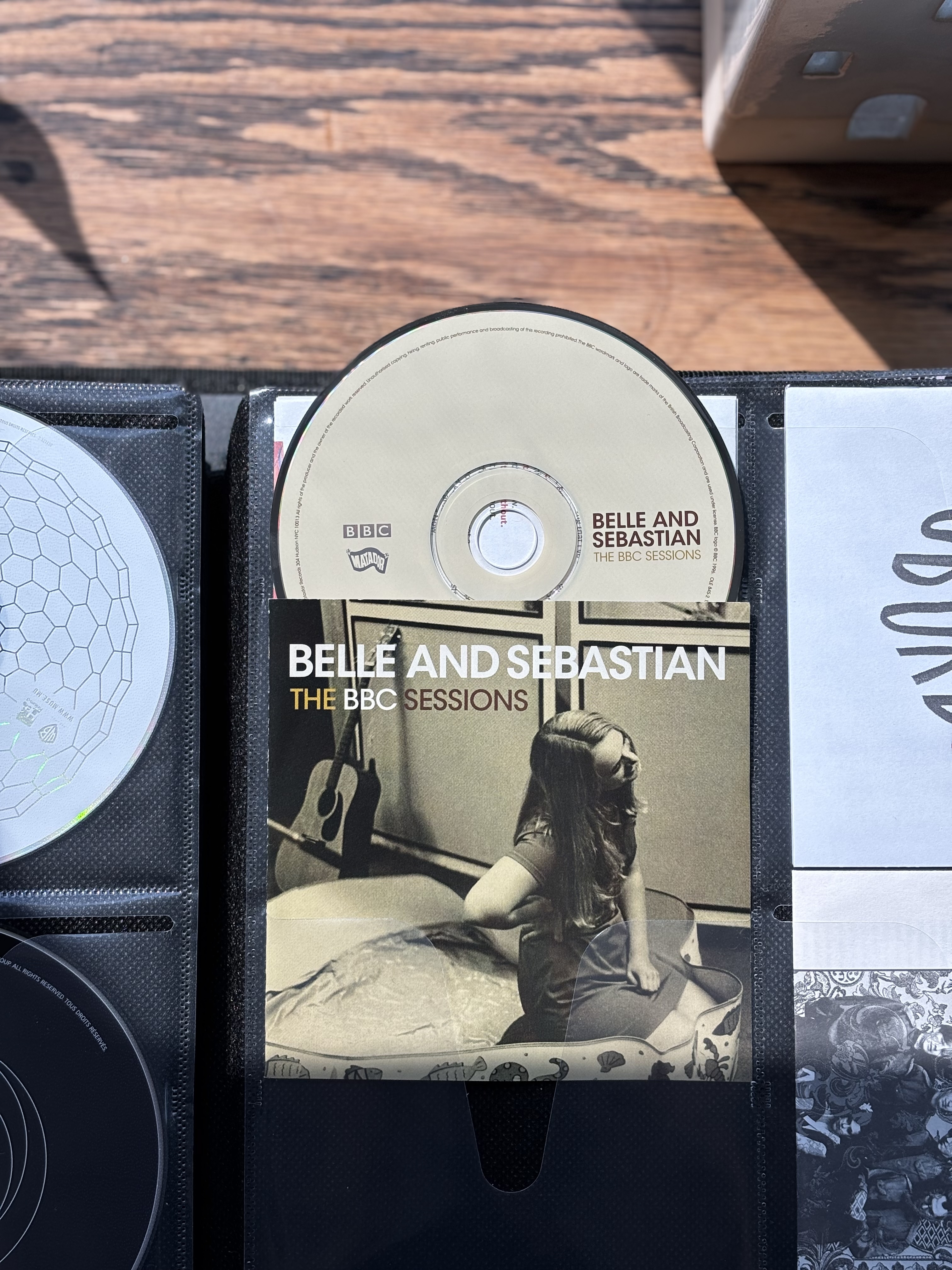

You pull up a favourite playlist on your streaming platform of choice. You flick through it and are sourly surprised: a song is gone. Greyed out, ghosted. The rights have lapsed, the artist has departed from the platform, or who knows what. The platform has no answers because the platform doesn’t give a shit that you were planning to listen to Belle and Sebastian’s “The State I Am In” from their BBC Sessions album because you’re feeling a little wistful.

The music is just…gone. And there’s not much you can do about it.

In 2015 I filled five bankers’ boxes with my CD collection. It covered everything from the complete Sufjan Stevens Songs for Christmas box set, to Valeri Gergiev conducting Shostakovich, to mixes and album rips burned by ex-boyfriends. When I moved into my house in September 2020 I finally reclaimed my CD collection from storage. I was thrilled at the reunion-until I realized the last time I owned a CD player was also 2015.

What do you do with five hundred CDs when Spotify has everything on demand? I thought as my husband and I lugged the boxes into the basement, where they could gather a new layer of dust. It felt ignoble to consign them to another stint in basement purgatory after they waited so patiently for me, but I’d sold my CD storage towers long ago. The CDs remained in the basement until this February when, facing another move, I had to decide once and for all if I would keep them.

Over a series of winter evenings I sat on my living room floor and methodically pulled album booklets and discs from their jewel cases and filled a 6.5” thick binder with CDs. I didn’t have room to store 5 bankers boxes in a 900 square foot apartment, but I could fill this millennial ark—a CD binder! You can still buy them!—and preserve the fragile heart of my music collection.

Last week I wrote about my early experiences listening to music, but the experience is somewhat less romantic in 2025. As Jeremy D. Larson over at Pitchfork so ably put it:

The truth is that if you’re using Spotify, Apple Music, Tidal, or any other streaming service, you’re not paying for music so much as the opportunity to witness the potential of music. Music becomes an advertisement for the streaming service, and the more time and attention you give it, the more it benefits the tech company, not necessarily the music ecosystem.

Today I transferred nearly a decade’s worth of playlists from Spotify to Apple Music. This is in no way a righteous decision. Choosing a music streaming platform isn’t about deciding which one is better so much as it is deciding which one is less spiritually corrosive. Switching platforms is a decision saddled with inconvenience, compromise, and sourness. Apple isn’t directly funnelling my subscription dollars into funding AI defence tech, but they aren’t paying artists streaming royalties anything close to what their music is worth, either. The migration is fractionally better, but it’s not quite right.

My gargantuan CD binder is a bulwark against the encroachment of Big Tech into my private life. If I want to listen to Muse’s HAARP on repeat in an honest to goodness CD player, I can—and no streaming platform can then use that listening data to force-feed me advertising like a cursed goose. I have a Blu-Ray player again for the first time in years, which means I’ve liberated myself from the tyranny of streaming’s false convenience: I no longer need to figure out which streaming service has the movie or show I’m looking for because I own a copy. The license won’t expire and the content can’t be modified post-purchase because it’s in my hands. It’s much harder for a multinational corporation to rent-seek on your attention if they don’t know where your attention is.

I stubbornly believe that these small acts of refusal are necessary and valuable for preserving sanity and selfhood. By moving more of my life offline I become fractionally less suggestible, targetable, or marketable. While the opportunities to make this slow migration involve flawed and shaky choices, they are my choices. Preserving the right to choose how and when we interact with technology is an increasingly important fight. As companies gleefully cram untested technology into their products in a desperate attempt to bolster profits and camouflage their moral bankruptcy, it’s important to remember that you do have choices. Invention only looks inevitable in hindsight, but so many of the things we think of as fixed features of modern life were the result of accidents and choices. No technology is ordained, nor is it inevitable.

So, c’mon, mess up the revenue calculations and annoy a tech company today. Pull out your CD player or dust off the DVDs. Borrow a book from the library or pick up that guitar you have lingering in the basement and make a tune yourself. When you crack open that CD binder you might just open to the space that holds your favourite Belle and Sebastian album. The music never disappeared, it was just waiting for you to arrive.